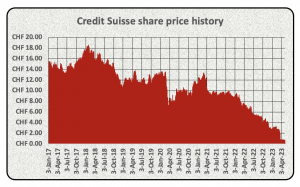

There are banking jitters out there at present. Even Warren Buffett had a few things to say about this to his ±30,000 loyal followers who attended the annual jamboree in Omaha recently. Credit Suisse announced on 19 March 2023 that it was merging with UBS, another Swiss behemoth, in order to avoid potential bankruptcy. Credit Suisse was worth US$45 billion at the end of 2017 and now has declined to a paltry US$3.5 billion. That’s value destruction par excellence. The loss of trust in a bank is usually a fatal occurrence – people do not like the thought that their hard earned or grifted cash is not safe in the bank. This fear is often followed by hasty online withdrawals or lengthy queues at the bank’s door. Credit Suisse had been dogged by many scandals over the past decade, some worthy of a novel or two. Imagine a public spat between the incumbent CEO and the head of the Wealth Management division of a banking group making headlines in the staid world of Swiss banking? Well it came to a head in 2019 and the latter departed for UBS (now, there’s shadenfreude). The CEO of Credit Suisse in his wisdom employed a surveillance firm to spy on the departed executive’s activities and public revelation of this made for some juicy reading.

I have had some professional dealings with banks over the years. I was deployed as a trainee decades ago to be part of the teams auditing two of South Africa’s leading banks. I had no idea what I was doing at the time but I loyally followed the audit programs and tried to appear smart and hard working to my superiors. After completing my articIes, I worked in investment banking for a while, learning a lot and not sleeping much. I later in my career veered into corporate training and inter alia, delivered finance for non-financial management training programs in-house for a major RSA bank. In this programme, I tried to explain personal and business banking in layman’s terms and to induce a love of numbers and all things finance. I hope I succeeded.

Banking is both a simple and complicated business. Simplistically, banks accept deposits (or actually borrow money) and on lend to customers. Banks typically hope that you and I leave our money in current accounts for extended periods, earning no interest, whilst this is lent to credit worthy individuals and corporates at market related interest rates. Sounds simple, banks earn an interest margin by lending money at higher rates than they pay for the privilege of being protectors of savings and surplus cash. Obviously, banking is a far more complicated business than that and involves a significant investment in people, processes and systems to provide critical services to the economy. No doubt they employ artificial intelligence in identifying risks and grey money but let me not digress into ChatGPT et al.

Credit Suisse was founded in 1856 and became a global leading banking group delivering financial solutions and wealth management services to private, corporate and institutional clients. I analysed Credit Suisse’s financial performance over the period 2017 to 2022 per their published annual reports to see whether I could identify any red flags – refer attached Excel file for my workings and analysis. Credit Suisse analysis (May 2023)

There are a couple of key ratios that pertain to banks:

- Net interest margin

- Non-interest revenue to total revenue

- Credit loss ratio

- Cost-to-income ratio

- Return on equity (ROE)

Net interest margin provides an indication of the extent to which banks earn higher rates on their lending than they pay depositors for their capital. Credit Suisse’s net interest margin was between 1.6% and 1.7% until the wheels came off in 2021. Crudely, that means that Credit Suisse was earning 1.6%/1.7% more interest on its loans to customers than it was paying to depositors. (Note to self – please update analysis of Capitec and ascertain what their net interest margins have been. Also check what happened at SA Taxi Finance aka Transaction Capital)

Non-interest revenue to total revenue refers to the percentage of total revenue that a bank earns from providing services as opposed to lending activities. Banks earn non-interest revenue from multiple sources from monthly banking fees to ATM withdrawal fees to advice fees. Credit Suisse’s non-lending activities represented 74% of total income in 2021, which in my opinion is a warning sign. Non-interest revenue is welcomed but if it is too high it may be a sign of volatile earnings. Lending revenues tend to be stable over time but non-lending revenue can vary depending on economic conditions. For example, customers may be reluctant to purchase new vehicles when economic conditions deteriorate and hence, fees earned from such new financing activities may decline. Existing vehicle finance loans may not grow but existing loans will still bear interest.

The credit loss ratio refers to the % of total loans that a bank expects not to recover in full. Some refer to this as bad debts but do not mention this word in the presence of accountants, who will immediately go off on a spiel about stage 1, 2 and 3 expected credit losses. Sounds like load shedding but quite normal in banking parlance.

Credit Suisse’s credit loss ratios were around 0.1% in 2017, 2018 and 2019 and then increased significantly in 2021. A quick question to ChatGPT and a review of Credit Suisse’s 2021 annual report revealed some reasons for the worsening of the credit loss ratio in 2021. Credit Suisse incurred credit losses (actual and estimated) of ±US$4.8 billion relating to its exposures to Archegos Capital Management. Archegos was a private firm founded by Bill Hwang that invested (speculated?) in shares and derivatives. Credit Suisse lent Archegos money to pursue these capitalistic activities and unfortunately Archegos was not able to beat the market all the time and succumbed to liquidation in 2021. Imagine lending to a ‘hedge fund’ and then losing US$4.8 billion, which represented almost 10% of Credit Suisse’s total shareholders equity? PS Some people were fired post this discovery.

The cost-to-income ratio refers to the percentage that total operating costs (employee costs, IT costs etc.) represent compared to total revenue. There tend to be banking industry benchmarks – in South Africa, cost-to-income ratios of more than 60% are frowned upon. Credit Suisse’s cost-to-income ratio declined from 88% in 2017 to 77% in 2021, all too high in my opinion. Bank’s costs are largely fixed and overheads need to be kept as lean as possible.

The last ratio is ROE, meaning what return is the bank generating for its shareholders? Credit Suisse’s ROE varied between 4.6% and -16.1% prior to is demise. Harley enticing returns for long suffering shareholders.

So, was Credit Suisse’s demise predictable? Their key ratios were a bit off for years but the information in the public domain about management spats and lending to ‘hedge funds’ should have set off alarm bells. There is an infamous saying accredited to Ernest Hemingway, “…how do you go bankrupt? Slowly, slowly and then suddenly…”. Deposits at Credit Suisse declined from CHF393 billion in December 2021 to CHF166 billion in March 2023, a decline of CHF227 billion. Loans to customers remained largely unchanged leaving a funding hole to be plugged. Credit Suisse’s shareholders and lenders were not keen to take this risk and the rest is history. Au revoir Credit Suisse.

Hope to post soon about Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank who have also gone out of business recently.

Hope to post soon about Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank who have also gone out of business recently.

Stay warm amidst all this load shedding.

Leave a Reply