Tongaat Hulett has been around for 128 years. It is currently fighting for survival with debt levels of ±R12.4 billion as at 31 March 2020. The story of what went wrong at Tongaat Hulett resurfaced in the media in recent weeks. Rob Rose, a journalist at the Financial Mail, is like a dog with a bone and keeps reporting on Tongaat Hulett. I guess the sub-story of Jenitha John, the chairperson of the Audit Committee of Tongaat Hulett from 2011 until her resignation in 2019, being appointed as CEO of the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA) has also created some angst within the audit profession. To be fair to John, I found it difficult at face value to identify the accounting irregularities upon reviewing Tongaat Hulett’s historical financial statements for the financial years (FY) ended March 2013 to 2018. I know that Magda Wierzycka would have detected these misstatements in 30 minutes but the rest of us mere mortals may be a bit slower in absorbing, analyzing and reflecting on complex financial accounting practices.

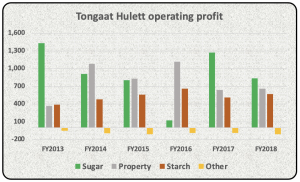

Tongaat Hulett’s operations comprise the Sugar division (sugar cane farming and processing), Starch division (manufacturing of starch and glucose products) and the Property division (development and sale of agricultural land on the North coast of KZN). Starch is the most stable of the lot. The other two divisions are rather volatile from an earnings perspective. Imagine preparing budgets for the Sugar and Property divisions – refer below for their performance over the period FY2013 to FY2018 (prior to restatement):

Peter Staude was CEO at Tongaat Hulett for 16 years prior to his retirement in late 2018. Staude had an interesting leadership style according to media reports. For example, Rose reported in 2019 that Tongaat Hulett had not had any group executive committee meetings for a two year period leading up to Staude’s departure. He apparently did not think it would be useful for group executives to formally meet. Imagine trying to run a golf or bowling club without formal committees? It would be a disaster and would create an environment for all sorts of malfeasance.

Gavin Hudson was appointed as Staude’s replacement. The former SAB Miller executive had a rude awakening early on at the helm of Tongaat discovering that things were not as rosy as he was told prior to joining Tongaat. PWC was appointed in May 2019 as forensic auditors to investigate certain of the accounting practices at Tongaat. It certainly has been a lucrative few years for PWC’s forensic division, particularly their work at Steinhoff. Steinhoff paid €40 million in fees relating to the forensic investigation and accounting support in 2018/2019 – yes sports lovers, thats over R732 million! The forensic and other consulting fees cost Tongaat a paltry R156 million in FY2020. Anyway, PWC uncovered various accounting shenanigans according to the Tongaat executives’ results presentation to shareholders and analysts for FY2020.

I have been saying for years now that accounting standards have become far too complicated. It results in very few people understanding how to record transactions and creates an environment where the ethically challenged can report whatever they deem fit. Tongaat is required by International Financial Reporting Standards to revalue their growing sugar cane to estimated fair value every half-year and at financial year-end. Yes, you heard correctly – sugar cane in the fields should be revalued to the value that could be hypothetically realized if sold as a plant prior to processing. It essentially amounts to upfront recording of profits prior to harvesting. Please do not ask me to explain why one should adopt this accounting convention since it appears illogical to me. Anyway, valuing growing plants and other biological products is not a precise science and there is room for professional judgment. Apparently Tongaat were a bit exuberant in their sugar cane valuations. The other thing Tongaat got wrong was to capitalize certain costs of growing sugar cane instead of expensing these through the income statement. The restatement of Tongaat’s FY2018 financial results was a messy and embarrassing affair for all concerned, including the incumbent auditors.

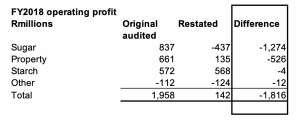

The Sugar division’s operating profit of R837 million descended into a loss of R437 million in FY2020 due to the aforementioned reasons. The Property division was also apparently a bit naughty, recording land sales upon signature of agreements rather than upon transfer. The division also saw fit to occasionally lend money to potential buyers to fund the acquisition of properties from Tongaat. No wonder Hudson and his team were struggling to collect some of their debtors book during 2019.

The Sugar division’s operating profit of R837 million descended into a loss of R437 million in FY2020 due to the aforementioned reasons. The Property division was also apparently a bit naughty, recording land sales upon signature of agreements rather than upon transfer. The division also saw fit to occasionally lend money to potential buyers to fund the acquisition of properties from Tongaat. No wonder Hudson and his team were struggling to collect some of their debtors book during 2019.

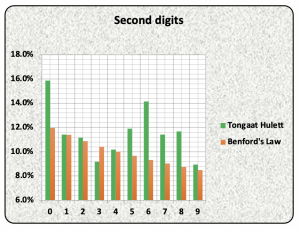

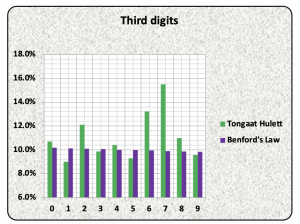

Simon Newcomb (1835 – 1909) is thought to have stumbled upon what is known as ‘Benford’s Law’. Newcomb discovered that the probability of digits (1,2,3 and so forth) occurring as the first digit in a number generally followed a particular pattern. For example, the digit 1 appeared as the first digit in numbers around 30.1% of the time. Similarly, 2 was likely to be the first digit of a number ±17.6% of the time. The length of rivers, height of mountains and populations of cities tend to be a good fit for Benford’s Law. Other data sets do not conform to Benford’s Law for example, pre-numbered invoice numbers or cellphone numbers. It transpires that financial accounting numbers are subject to Benford’s Law. Some forensic auditors swear by it and use it to identify accounting irregularities and fraud. Mischievously, I analyzed Tongaat’s reported income statement, balance sheet and cash flow statement numbers for FY2013 to FY2018 prior to restatement to see whether there was anything amiss.

It would seem as if Tongaat’s numbers were slightly off compared to what Benford’s Law would predict. The digit zero should have occurred as the second digit in Tongaat’s numbers ±12.0% of the time, instead it appeared on average 15.9% of the time. Similarly, the digit 6 should have occurred as the second digit in Tongaat’s numbers 9.3% of the time – actual result was 14.1%.

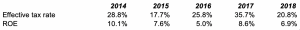

As mentioned earlier, I struggled to find anomalies in Tongaat’s historical reported numbers. Two ratios, however, did seem odd. The first is the effective tax rate being normal taxation to be paid to SARS divided by profits before taxation. South Africa’s corporate tax rate is currently 28% and hence, I would expect Tongaat’s effective tax rate to be in that ballpark. It proved not to be. This was also the case when analyzing Steinhoff’s reported income statements. The second ratio was return on equity (ROE) – calculated as profits after taxation divided by shareholder equity. Tongaat’s was way below expectation.

Tongaat’s shareholders should have been furious that the executives were only delivering a 6.9% return on capital employed in the group in FY2018. Tongaat shareholders could obtain a yield of over 11% today if they invested in RSA government bonds maturing in 20 years time. Why allocate capital to executives who can only deliver a return of half that?

The sad part of the Tongaat saga is that the group has agreed to sell the Starch division to Barloworld for R5.35 billion. This division is the only stable profit generator in the group yet Tongaat needs to raise capital to repay debt. Its amazing how often that happens in practice – companies get into trouble and then are forced to sell the crown jewels to save the remainder. The devastating aspect of the Tongaat saga is the R22.6 billion of shareholder value that has been destroyed by management over the past 6 years.

Hi Greg this was an insightful article. Thanks for your candid and honest opinion.