A 2015 study published in the Journal of Accounting and Economics (Dichev, Graham, Harvey & Rajgopal) revealed that chief financial officers (CFOs) believe that 20% of firms intentionally distort reported profits. They estimated that CFOs, along with other executives, ‘low ball’ earnings (deliberately reduce reported profits) approximately 33% of the time and 67% manipulate earnings upwards when they elect to ‘cook the books’. That is very disturbing for those of us who analyze annual financial statements and rely on them for investment decision making. In fact, it should be worrying for all of us since we should be saving monthly and investing in unit trusts, retirement annuities and those sorts of things.

So how do CFOs manage to manipulate profits upwards or downwards quarterly, biannually and/or annually? Surely, the auditors would detect this? Unfortunately, accounting standards have become so complex that very few people understand them all. I pull my hair out at times, the few strands I have left, at the illogicality and complexity of certain accounting standards. I often joke in the classroom about a conspiracy theory about why accounting has become so opaque and intricate. There is a global body called the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) head quartered in New York that issues accounting standards that its member bodies in 130 countries need to comply with. These accounting standards are either called International Accounting Standards (IAS) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). IAS are the older statements and IFRS’ are slowly replacing these. The only people who really understand these standards are accounting university lecturers (their students are mostly baffled by these lengthy documents), the audit firms (hopefully), CFOs, global accounting institutes and IFAC itself. So my conspiracy theory is that these accounting standards have been issued so that auditors and consultants can charge a fortune to interpret them. Please forgive my wondering mind.

Please indulge me as I discuss how sometimes accounting standards are removed from economic reality and are really difficult to understand. IFAC introduced IFRS 16 Leases which is effective for all financial years commencing on or after 1 January 2019. IFRS 16 deals with the accounting for leases which are more than 12 months in duration and cover assets which have a value of more than $5,000. I know some of you may be switching off at this stage but hang in there. Let me illustrate with a relatively simple, hypothetical lease agreement of office space:

- Occupation date of 1 January 2019

- Five year duration, lease terminating on 31 December 2023

- Annual rental of R1,000,000 payable annually in arrear (in our collective dreams would landlords offer us terms such as these but this is a hypothetical example)

- Annual escalation in rental of 5% from 2020

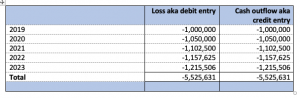

Now we would think this is a pretty simple transaction to account for. The rental payments due are set out below (hope I got the maths right) and the related accounting would surely be as simple as this:

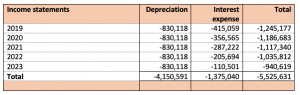

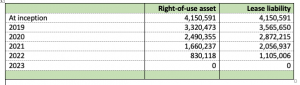

Well, IFAC and its members decided that this accounting was too simple and allege that lease obligations are in fact interest-bearing debt instruments. All leases (except those of less than 12 months duration and low value items) need to be capitalized on the balance sheet (forgive me but I can’t get around to calling this a statement of financial position). From 2019 onwards, all companies that adopt IFRS need to present value future lease payments using their incremental borrowing rates (effectively the rate that their bankers would lend money to them in order to enter into the lease). Without getting too complicated, companies need to recognize a right-of-use asset and a corresponding lease liability (being the NPV of future lease payments) at the inception of the lease. The right-of-use asset is then to be ‘depreciated’ over the period of the lease and the lease liability is to be extinguished by the lease payments after adding hypothetical interest. Seems like the right thing to do? Assuming that a hypothetical company above entered into the above mentioned lease agreement and had an incremental borrowing rate of 10%, the net present value of the future lease payments would be R4,150,591. The accounting would go something like this:

Well, IFAC and its members decided that this accounting was too simple and allege that lease obligations are in fact interest-bearing debt instruments. All leases (except those of less than 12 months duration and low value items) need to be capitalized on the balance sheet (forgive me but I can’t get around to calling this a statement of financial position). From 2019 onwards, all companies that adopt IFRS need to present value future lease payments using their incremental borrowing rates (effectively the rate that their bankers would lend money to them in order to enter into the lease). Without getting too complicated, companies need to recognize a right-of-use asset and a corresponding lease liability (being the NPV of future lease payments) at the inception of the lease. The right-of-use asset is then to be ‘depreciated’ over the period of the lease and the lease liability is to be extinguished by the lease payments after adding hypothetical interest. Seems like the right thing to do? Assuming that a hypothetical company above entered into the above mentioned lease agreement and had an incremental borrowing rate of 10%, the net present value of the future lease payments would be R4,150,591. The accounting would go something like this:

You pay R1,000,000 in 2019 to use the office space but record an expense of R1,245,177. In 2023, the actual lease payments amount to R1,215,506 yet the total expense recognized in the income statement will be R940,619. That makes sense (forgive my attempt at sarcasm). I have attached the Excel workings in case some of you wish to indulge in the deep dark world of IFRS workings. The balance sheets make even more sense (sic).

Pick n Pay recently released its results for the 6 months ended September 2019. Imagine the shock and horror when the CEO and CFO announced that interest-bearing debt had risen from R1.3 billion at February 2019 to R15.9 billion at the end of September thanks to their adoption of IFRS 16. So perhaps you have been enlightened about how these accounting scandals occur. The recipe is simple. Make the accounting rules very complicated and ensure that they require significant judgment by users in following them. Then add a human being (obviously an ethical one) to be the implementer of these rules and add the pressure of having to satisfy the market’s unrelenting appetite for increasing profits. Ensure that these results are then audited by 1st year clerks. The result is a world of pain for financial analysts.

So why do executives misstate profits or losses? The research referred to at the start of this blog revealed that the motivations to misrepresent economic performance included:

- To influence the share price, if the company was a listed entity

- Because of pressure to meet earnings targets due to both internal and external expectations

- To improve executive compensation (ouch, eina, bliksem)

- To avoid adverse career consequences if poor performance is reported

- To avoid a breach of debt covenants in place with the bankers

So how do we mere mortals detect these incidents of accounting manipulation? We can learn from past experience, as painful as that it. When financial statements become unfathomable due to descriptions of items called brand income for a furniture retailer (think Steinhoff), be scared. When the group changes its financial year-end every 18 months (think Steinhoff), be terrified. When the group keeps acquiring every moving target beyond our beautiful shores (think Steinhoff), be alert. When the group revalues its sugar cane plantations without providing the underlying assumptions (think Tongaat) and records these upward adjustments as profits before a sliver of sugar cane has been harvested, be sceptical. Other warning signs could include:

- Profits and cash flows do not correlate (profits are up but cash generated is consistently much lower or even negative)

- Financial results are unrelated to industry norms or economic conditions (eg. revenue growth of 25% whilst the rest of the economy is bleeding)

- The group consistently meets or beats market expectations re financial results

- Frequent once-off items such as restructuring costs, impairments and gains on disposal of assets

- Earnings results are just too smooth such as General Electric which under Jack Welch’s leadership, delivered 100 consecutive quarters of earnings growth. That is surely a statistical impossibility.

Be grateful if you never invested in Steinhoff or Tongaat. All the best from BeechieB.

Recent Comments